Tuesday Night at the Bible Study

Sufjan Stevens, reader response theory, and finding yourself through art

This essay was originally published as a guest post for on Friday, November 3. Here it is for you to enjoy.

I haven’t spent a lot of time in Illinois.

I can remember playing keys and samples on

’s Glacier tour in 2013 and spending the night in a music journalist’s home in Chicago. I forget the writer’s name. We played at a venue that doubled by day as a retro hair salon. After the show, a crowd-member told us that we reminded him of the band American Football. In the morning, as we pulled out to head to the next city, we drove over Jamison’s laptop.That’s the extent of my memory of the state. The short visit happened ten years ago—nearly a decade after I first heard Sufjan Stevens’ breakthrough record, Illinois.

Look beneath the floorboards

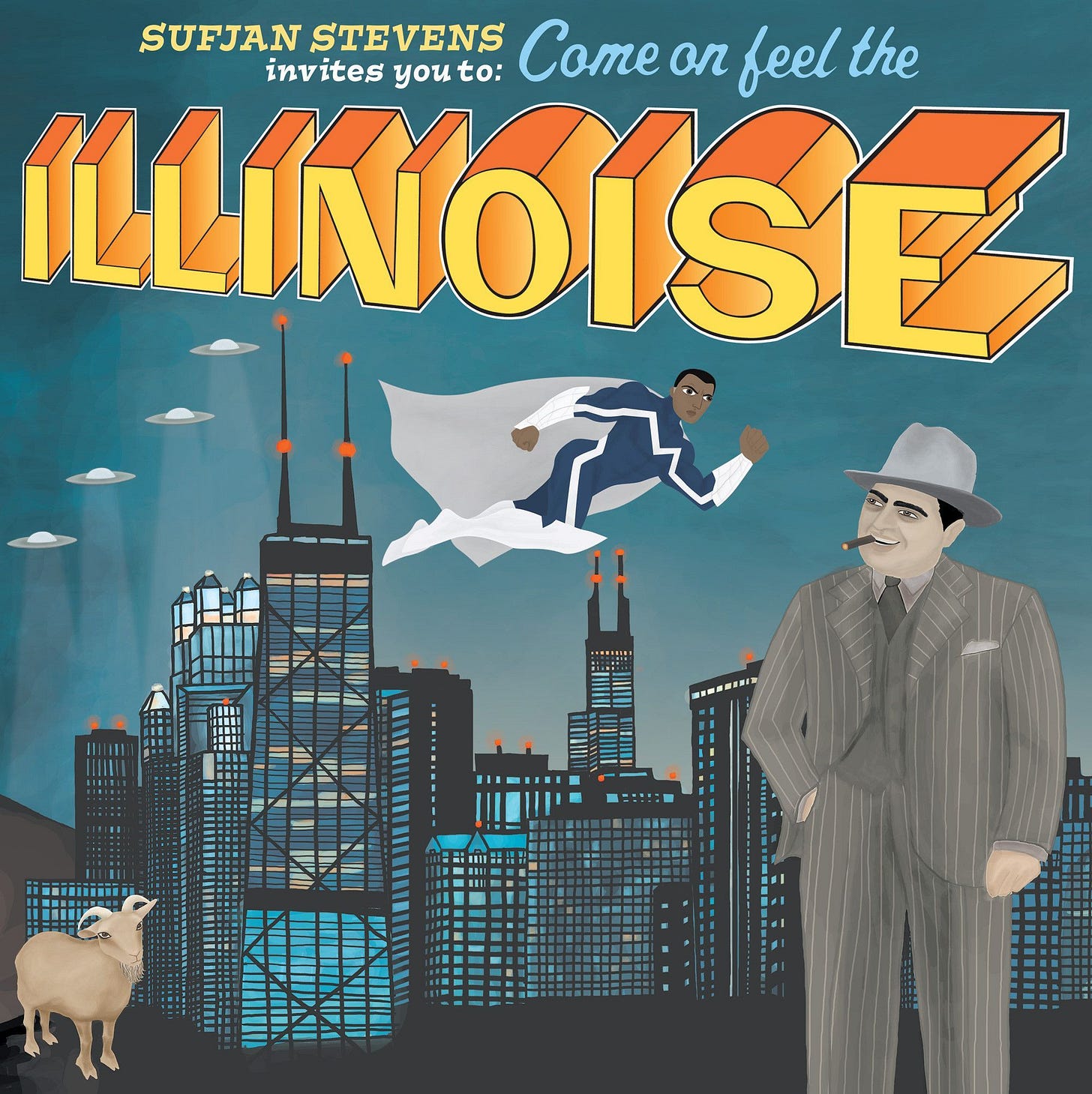

When the genre-defying concept album arrived in the summer of 2005, I had just graduated high school 3,500 kilometres northwest of Illinois, in Langley, BC. Except for a family trip that included a drive along the border from Michigan to Washington five years prior, I had no personal experience of the state. Chicago was more or less another anonymous American city, a multi-lane highway with its own style of pizza. The only other details I knew were taught to me by Wilco.

And yet, from the first time I listened to my pirated mp3 of “The Black Hawk War, Or, How To Demolish An Entire Civilization And Still Feel Good About Yourself In The Morning, Or, We Apologize For The Inconvenience But You're Going To Have To Leave Now, Or, "I Have Fought The Big Knives And Will Continue To Fight Them Until They Are Off Our Lands!"”1 I connected to the music and stories of Illinois more than almost any other album.

There a few reasons why this makes sense. The album’s style—a combination of banjo-led, concert-band orchestration, friend-group vocals, and DIY studio technique—seemed deliberately targeted toward a music nerd with a penchant for all things hipster like me. It felt like Sufjan was making the music of my imagination and then taking it further than I could ever dream to. He would interrupt a pretty trumpet part with a crunch of guitar without hesitation. He would reserve a whole track for applause to the preceding song. He would use tom-toms like they were timpanis. Together, it all sounded so fearless.

But the album’s most lasting impact came from its lyrics. Some songs seemed to spin from topic to topic like a bingo wheel filled with obscure historical references. Others zeroed in on outrageously personal memories, state-wide tragedies, and imagined apocalypses. My ADHD brain loved it all, but the more personal and specific Sufjan got, the more I seemed to relate. He made me want to know as much about him as possible, and by digging up the details of his life, my connection to him and his music only strengthened.

It helps that we share a few biographical details—specifically, a Christian upbringing. This kind of heritage is anything but unique to Sufjan or myself, but the way he incorporated his background and faith into his lyrics made him stand out to me. Rather than infuse his lyrics with clichés and moralism (the unfortunate norm for anything labelled “Christian music,” then and now), Stevens admitted disappointment, doubt, and confusion, referred to God’s gender ambiguously, and empathized with monsters and devils. In a word, he was being honest.

I absorbed these radical confessions on multiple levels. The ideas Stevens shared influenced my own faith and thinking and helped broaden my perspective. But his words also interacted with my own experiences and memories, producing a specific, personal meaning for me that helped me be more honest with myself.

Thinking outrageously

For most music fans, this exchange is par for the course: we connect to a song or album because it articulates something about ourselves that we didn’t have words for until we pressed “play.” Learning about the artist and context might help us deepen our connection to the music, but it starts with the instruments and words travelling through our ears and clinging to everything else in our minds.

In the world of academia and criticism, though, this idea—that the meaning of art is created in the mind of the audience—is relatively new. And controversial. Even now, decades after it was introduced, the concept—labelled reader response theory—troubles people who would rather attribute the meaning of a work to its creator, or at least to the work itself.

When it was introduced to me in college, reader response theory felt like finding the last piece of a puzzle I’d been working on my whole life. Just like a perfect lyric, Louise Rosenblatt’s description of reading as a transaction put to words something that I felt but couldn’t say, something that, on its surface, seemed so simple and obvious. It was like a hack—the last, biggest Russian doll that could hold all the others inside of it.

Think about it: our brains are receptacles. They hold everything we’ve experienced, from Mom’s hug after a nasty spill to the moral dilemma we felt while reading all the the “n” words in Huckleberry Finn. When we pick up a new book or listen to a new album, we bring all of that knowledge and experience to our understanding of it. And as we interact with that work of art, it gets catalogued with the rest of our brain-data to influence our experience with the next. And so on and so forth. Yada-yada-yada.2

Other literary theories of the past century or so tend to focus on finding meaning through one lens. Marxist theory makes it all about class. A feminist reading will highlight the power struggle between the sexes. A formalist will try to whittle the meaning of everything down to the words on the page. But taking a reader response approach doesn’t force you to choose. As the reader, you get to apply any knowledge or experience at your disposal to your interpretation. As

puts it, “the only sin is to not notice.”The pushback against taking this concept seriously in criticism came from a feeling that it took a previous notion—Roland Barthes’ “death of the author”—too far. It was one thing to put the author’s intent aside and focus on the text itself. It was another thing entirely to give all the power of meaning-making to the reader, the people. That would be anarchy.3

Whatever objection there might be to the theory doesn’t really matter—because it works: the reader’s response really is where the magic of meaning-making happens. A breadth of knowledge—of the art form, of the artist, of the culture it’s all a part of—can inform our interpretations and improve our interpreting skills. But none of this external info actually reveals the value or meaning in a work of art. That happens through the reading process.

All things go(?)

To make the point clearer, let’s work through an example.

“Casimir Pulaski Day” is a sad song about what we assume was a very real and personal experience. Sufjan doesn’t give all the details, but from what he includes, we can stitch a basic plot summary together: a friend-turned-lover gets bone cancer; despite the desperate prayers for divine intervention, none comes, and the friend/lover dies; to make matters more confusing, a potential sighting seems to confirm the existence of God despite the lack of any clear answer from him. All Stevens knows for sure is that “he takes, and he takes, and he takes.”

If we took a traditional literary approach, this song’s meaning would be completely wrapped up in what it tells us about Sufjan Stevens. To find it, we’d ask questions like “What biographical facts does it relay about Stevens?” or “How does it fit into the overall context of his life and the culture surrounding him at the time?” or “What can we glean about Stevens’ perspective on the songs themes (death, spirituality, sex, etc.)?”

These could all be helpful questions to ask. Answering them could guide us to a richer understanding of the song. But do they reveal the meaning of the song on their own?

Taking a step into postmodernity, a formalist theory to the song would try to take Sufjan out of the picture entirely and focus instead on the lyrics themselves. In that case, the song would be primarily about two people—the “speaker” or narrator and the blouse-wearer with cancer. A thorough analyst would go line by line, interpreting each one as it relates to the others. They would likely come to similar conclusions to the traditionalist, discover the same themes, the same perspectives, etc.

Again, the process might be helpful, but left alone, formalism leaves me feeling like something’s missing. It feels cold. And a heart-felt song like “Casimir Pulaski Day” shouldn’t feel cold.

Now let’s try the reader-response way.

(For the sake of emphasis, I’ll to retroactively apply my interpretation as I first experienced it, before I knew much of anything about Mr. Stevens. But remember: within this theory, I can apply any knowledge I’ve gained from any other approaches, since they’re now a part of what I bring to the text.)

There are plenty of references in the song that I know nothing about. I don’t know what “golden rod” or the “4H stone” are. I don’t know the significance of the father driving to the Navy yard. From memory, the first lines that popped out to me were the following:

Tuesday night at the Bible study we lift our hands and pray over your body but nothing ever happens

They popped out because they exposed a shared experience among church-going people that, for the most part, is kept silent. In church circles, people pray for, over, and about sick people all the time. In many cases, those sick people die. It’s a fact of life, one that everyone who’s gone through the experience knows intimately. And yet, in most cases, the disappointing result never gets acknowledge. Even worse, when it is acknowledged, whether verbally or internally, it often leads to judgment and shame: judgment that we didn’t pray hard enough, believe strongly enough; shame of our lack of understanding, that we would dare question God’s plan.

In these lines and in the verses that follow, Sufjan dares. And his daring fills me with conviction, not for my silent complacency, but for something I said during a Bible study get-together of my own.

I don’t remember how it got brought up exactly, but around the time this album came out, I lied to a group of church friends about my “prayer life.” We were discussing our own “states of faith” and a few of them were actually being honest about it. They were confessing that they didn’t pray that much at all and struggled to understand the point of doing it.

Then I chimed in, saying how I thought of my internal dialogue as prayer and was therefore praying all the time. It wasn’t a complete fabrication, but it wasn’t completely true either. I honestly can’t tell you how true it was. The point I’m making is that it wasn’t said because it was true. It was said to impress, because it seemed like the right thing—the wisest thing—to say at the time. I wanted everyone in the room to see me as the faithful, Christian man with the deep connection to God that I’d projected over the years they’d known me. Defining prayer this way reinforced that projection.

“Casimir Pulaski Day” still confronts me with this realization and pushes me to be more honest with myself and the people around me, to be willing to say, “I don’t know either. Life is difficult and confusing for me, too.”

If I ask myself what “Casimir Pulaski Day” means, I can’t in good conscience separate it from its impact on me personally. Adopting a reader-response approach means I don’t have to. It allows me to interpret the song without denying what it actually means to me. From my experience, this sharing of personal impact only enhances the meaning of the song in others. So then why would we leave it out of any “higher” discussion of art?

Oh, great intentions

While I wrote this essay, Sufjan released a new album and, for the first time, explicitly shared another integral part of himself with his audience—his sexuality. The day he dropped Javelin in our streaming feeds and opened physical sales, he published a blog post dedicating the album to his late partner, Evans Richardson, who died this past spring. Stevens hasn’t exactly been shy about his connection to the queer community—what with his work on the Call Me By Your Name soundtrack, his semi-regular references to his romantic feelings for men, his dubbing himself the “Christmas Unicorn”—but this marks the first time he’s made it unequivocally clear.

Coming out is always brave, but it takes an extra dose of courage to do so as a public figure who is outspoken about their spirituality and religion. As outsiders, we could ponder a number of reasons why he declined to broach the subject explicitly until now, but him doing it now should come as no surprise. Despite coming across as a private person, Sufjan has always found the strength to be vulnerable, especially when it served his art to do so.

All this to say: a blind focus on the reader’s response isn’t necessarily the way to go. Context can add to our understanding of art, and an artist’s intentions can often be the most valuable kind of context. The trouble I have is with the mindset communicated through most literary theories: that there’s one right answer for where to look for the meaning of things. To preach one theory exclusively seems willfully ignorant. Pretending the other lenses don’t exist doesn’t negate their existence.

With reader response theory, seeing your interaction with art as a transaction widens the frame as far as you’re willing to go. It allows you to look through as many perspectives as you have access to. And it doesn’t leave the artist out of the conversation: the audience creates the meaning, even if that audience is an audience of one.

Yes, that’s the title of one song.

Yeah, Andrew—it’s called learning.

Or “anarchic subjectivism.” You know, to make it sound smarter. Also: “anarchic subjectivism” sounds pretty democratic to me. I say bring it on.🤘

Really liked this. Love Sufjan, devastating song, the lyric “and he takes and he takes and he takes” always kills me

I’m a stage IV cancer survivor and involved in the young adult cancer world. We talk about the implications of how people frame healing with regard to cancer. It’s tough because if you say, “God healed me,” the next question is why me and not them?

And that’s me. I’m a miracle. And I feel that tension. Miracle is such a loaded word that I rarely use it. But no one thought I’d survive. At one point I had 50 mets (cancerous tumors) in my brain. My oncologists are just free-soloing with me now because in their words., “There is no one like me.”

So, why am I cancer free now, but my friends have died - some with the same diagnosis. I did have a lot of people praying for me. But that’s tricky. Do we pray to get God to act? And do more prayers lead to better outcomes? Does that mean the one quiet prayer goes unheard? That’s obviously problematic and paints God in a poor light.

Those some might make that claim anyway, based on cancer existing at all. But I don’t think we were ever promised we wouldn’t suffer. People written about in the Bible suffered all the time. God suffered in human form.

I like what Dietrich Bonhoeffer says, that it’s the suffering God that helps us. (Rather than a distant almighty god). God walks with us and comforts us and brings us through suffering. But as for the “why do some die and some don’t” question.... that’s still a mystery to me.

I live in this tension between gratitude and survivor’s guilt. I still pray for things, for people. My faith has changed a lot and I’ve cut ties with Christian culture, but I still believe in bringing things before God. I guess the mystery in the result still something I wrestle with.

I did have this one moment in the middle of cancer treatment where I was suddenly and irrationally overcome with gratitude. It occurred to me that years and years of prayers written in journals, whispered, were answered in one fell swoop. I mean, it was basically the same prayer. And it was answered in the perfect time. I still wasn’t confident that I would survive cancer. But it changed how I thought about prayer.

Honesty, prayer (like meditation or contemplation) changes us more than our circumstances.

Now I will express my other complaint about religious judgement. There are people that believe that when you suffer it’s because you or someone in your family has sinned. As if cancer is a punishment for some dark secret. It’s no surprise because the friends of the famous biblical sufferer, Job, also thought that. But it is super toxic. A woman in my mom’s church didn’t want anyone to know about her diagnosis because she didn’t want them to judge her that way (to which my mom was like, is that how you see us??).

We are supposed to walk with each other in grief and suffering. Everyone grieves and everyone suffers. We are supposed to whisper about their faithfulness.

Anyway, I love Sufjan. I saw him during his Age of Ads tour and it was incredible. I also love his Illinois concept album and get very emotional about his friend/lover that died. As I’m sure I will listening to his latest album. I’m really drawn to artists who wrestle with things in life instead of trying to fit them in a neat box with a consistent message (like a lot of Christian artists and writers).

I heard this attributed to CS Lewis, but it’s not confirmed. He (may have) said that he is not a Christian writer. He is a writer who happens to be Christian. That switch in thinking allows for a broader perspective., greater imagination, and the ability to be truthful.

As far as reader-response... I generally do this, but I also like to use other criticism as well. Why not explore from many angles?