Sevens All In My Cypher

Digable Planets, gatekeepers, and what we lose when we lose brick & mortar retail

I don’t remember what city I was in when I bought Blowout Comb. I know I was far away from home, but I can’t recall when or where exactly. It was either Toronto or Montreal, that’s for sure. It doesn’t really matter anyway. What matters is where in the city I found it, and how.

I found it in what is now an extinct breed—the multi-floor, major-chain entertainment stores that used to take up impressive real estate in every major city—the HMVs and Virgin Megastores positioned on corners in the most lucrative shopping destinations in the world. Tokyo, Paris, New York—they all had them. Now, they’re all gone.

I went into this corporate CD store with a specific goal: I wanted rap with horns. I remember hearing a song that could be described that way in a cafe that day, a song I didn’t know but wanted to hear again. But this was before Shazam, before Spotify and smart phones. To find the song or any music like it, I needed to ask a living, breathing human being. So that’s what I did.

I remember the customer service representative vaguely. He was a few years older than me, but we were otherwise quite similar: white, male, and in our 20s. I told him what I wanted, and it didn’t take long for him to recommend Digable Planets’ second album.

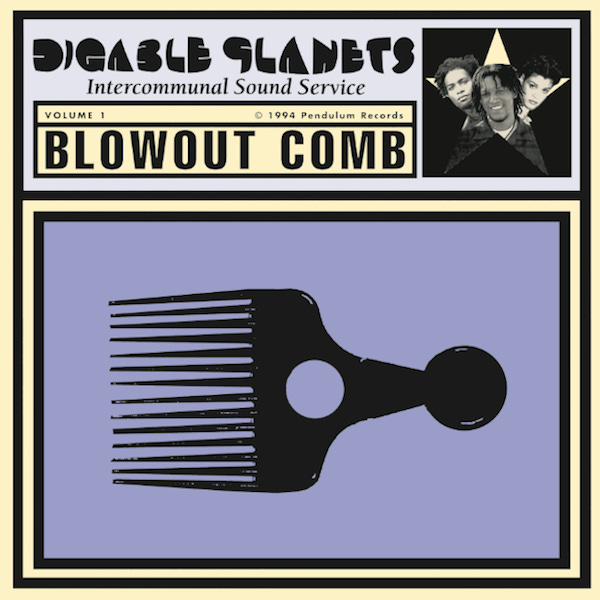

Since then, I’ve grown to understand that his suggestion made sense. Though Blowout Comb was a commercial failure in 1994—a failure that inevitably convinced the trio to disband a year later—it has since become something of a cult classic—just the type of thing you’d expect to be recommended by the caricature of a record store employee. But despite all the stereotypes at play in the situation, I’m glad he did, because I likely wouldn’t have found this album in any other way.

Google “rap with horns” and the top result you get is a listicle from Complex. The article does a pretty good job mixing lesser-known legends like Viktor Vaughn (aka. MF Doom) and Clipse with mainstream successes like 50-Cent, Jay Z, and Kendrick Lamar. But Digable Planets is nowhere to be found.

This observation isn’t meant to bash the tastemakers at Complex or any other music magazine. You can’t expect every article to have it all. I’m sure this essay will have its holes and blindspots. My point for bringing it up is actually to highlight exactly that. Each article, writer, magazine, and medium has its limitations. We can’t expect each one to know and/or do everything.

Gatekeeping is inevitable. And in a way, we’re all gatekeepers. Once you share an opinion on anything, you direct your audience toward something and away from something else. It’s unavoidable, and it isn’t innately a bad thing, either. The problem comes not from listening to “gatekeepers,” but from having too few of them. And as our access to music becomes more centralized, our access to new sounds and artists becomes increasingly reliant on fewer and fewer voices.

The affects of this problem don’t stop at the border of taste. In his TEDTalk on record collecting, Alexis Charpentier pointed to a study from the UK that revealed growing financial disparity in the country’s music industry. The study showed that the top 1% of UK artists earned 77% of the total revenues.

That was four years ago. I don’t think I need to tell you which way things have gone since then. But the study’s implications bring our brains back to the beginning: a story about Andrew buying a CD in a brick-and-mortar store.

My experience wasn’t free of conformity or controlled channels. It took place in space owned by a huge corporation, within a consumeristic, capitalist society, between two North Americans with profound privilege. But it was also an IRL interaction between two people that, in its small way, changed my life for the better. That lowly minimum-wage employee shared something with me that I likely wouldn’t have come across otherwise.

The effects of our increasing reliance on centralized, institutionalized, disconnected influencers reaches much farther than our music tastes. You can see its work in all areas of our lives, from our sources for entertainment and news media to the food on our tables. But much of it can be traced back to our shopping habits. The pressure to “buy local” ebbs and flows, but the Octopus of Amazon, Costco, and Walmart extends its tenticles over more of our lives. Like a tragic rewrite of You’ve Got Mail, we watch each Mom & Pop shop get squeezed out by these leviathans. More often than not, it happens without us even noticing.

Local economies aren’t the only victims of this gravitational pull toward online, big-box shopping—so is your freedom of choice. You might feel like you have all the options you need when you walk into one of these warehouses or grace Amazon’s website, but when it’s the only place left to shop, you’ll be beholden to whatever head office decides to order. No more specialized insights or advice, no more first-name basis.

It’s coming on Christmas (as Joni would say), the time of year when we spend the most time and money. While I don’t necessarily mean to encourage the commercialization of the holiday, might I suggest giving your dollars to the small shops of the world? Any boost they might’ve experienced during the “support local retail” push during the pandemic has officially worn off. They’re struggling. It’s up to us to collectively keep them alive.

For my little part, I’ll leave a few of my favourites below. Gifts are important and special. Let’s keep the businesses we buy them from important and special, too.

For Music:

Poprocks (Medicine Hat), Blackbyrd (Calgary, Edmonton)

For Books:

The Next Page (Calgary), The Book Man (Abbotsford)

For Other Gifts:

Elliot Home + Lifestyle (Medicine Hat), Bureau (Abbotsford)

My mind keeps returning to this post and your thoughts on “digital gatekeepers.” I lament the loss of so many independent bookstores and the ability to go in and find that perfect read based on a bookseller’s recommendation. Thanks for sharing!