Hi all.

I originally planned to put this essay behind the paywall, but then it turned out so well that I didn’t want to keep it from any of you.

If you read it and like it, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription.

I’d really appreciate it.

Sincerely,

Andrew

Spotify | Apple Music | Bandcamp

In My Way, I Say

Monday was a whirlwind of emotions.

It started with this hellscape of a prediction by

in which she describes how her AI-centred life will look five years from now. The scariest part of of the post? Griffin gives no indication that she sees any problem with this tech-written, algorithm-determined future.Did she not read Brave New World in high school like the rest of us?

Then I happened upon this real upper of a piece by

where he claims that our production and enjoyment of what we call “art” is an illusion, that capitalism has killed any possibility of the genuine, free expression required to create true art, that instead of offering anything new, the current, infinite supply of content is nothing more than “pastiche.”What an encouraging thought!

Why did I react so negatively to these two articles?

Griffin and Dess might feel differently about the current state of our culture, but their perceptions are strikingly similar. Both of them see today’s endless stream of content as nothing but remixes, reboots, and adaptations.

With that perspective, it’s not surprising that Griffin welcomes the influx of prompt-developed listening, reading, and viewing material she expects to consume and “create” within the next few years. Dess’ nihlistic alternative doesn’t sound nearly as fun.

That said, if I imagine these two as adversaries in some kind of formal debate, I’d likely side with Dess, preferring to acknowledge a difficult truth rather than pretend to be satisfied with a robot-fed “curation of self” as he puts it (ironically via a quote from Stephen Marche).

But are these two sides of the same coin really our only options? Is the bottomless pit of images, articles, books, poems, films, videos, photos, music, shows, games, etc. really void of any “private vision” as Dess claims? Will we all simply absorb, adapt, and adopt the music, stories, and images produced by so-called “artificial intelligence” as they inevitably blend with the cultural artifacts born from human thought and labour?

I’m here to argue a hard “no,” not out of a naive desire for a different future, but because of a vastly different view of the situation we’re in now.

If it were all up to me I would say come up to these truths instead

Let’s take a closer look at Griffin’s vision of the future first.

By 2028, Griffin imagines her life will be made easy by AI. A playlist of AI-made music perfectly matching her taste will wake her up in the morning. AI language models will do all the heavy lifting for her Substack posts, from research to sentence structure. AI will also summarize all the updates she needs to know and communicate to her coworkers. When she has a random idea for a fantasy novel, she’ll only need to write one page of text—AI will produce the rest in seconds. Same thing will go for film and TV, since actors and celebrities will license their likenesses to entertainment platforms, allowing viewers to use them in AI-prompted content. In her world, all the skills and experiences artists have funneled into their work for thousands of years will be deemed disposable in half a decade. Why go through all the trouble of self expression if AI does it better?

There’s only one problem with her prediction: it assumes that AI-generated content will find something it has yet to show any sign of finding: an audience.

There’s a lot of noise being made about what ChatGPT(insert # here), etc. can produce using simple prompts from users. But when it comes to our responses to the actual output, the most common I’ve witnessed is a hmm, interesting underlined by a growing anxiety. And the closer AI gets to mimicking the kind of art we’ve loved for centuries, the more anxious we seem to feel about it.

Why is this so? I think I know at least part of the answer. You see, no matter how “good” AI gets at producing “beautiful” things, it will always lack something integral to the experience that art offers us—a connection to other, human minds. We don’t just come to a story, a painting, or a song to absorb it on its own terms. We have always engaged with these things, at least in part, to discover what they reveal about the people who made them. With AI, there’s nothing to learn, no personality or history to link this “art” to1.

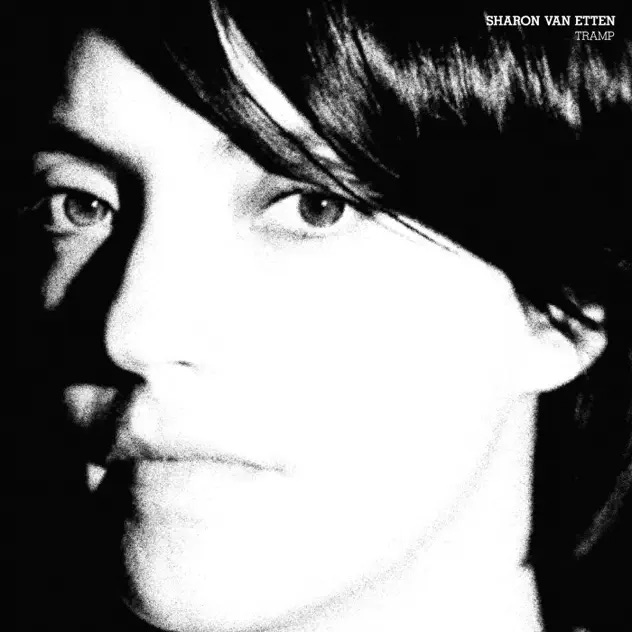

You could choose literally any piece of art as an example of this, but the work of a musician like Sharon Van Etten makes the case abundantly clear. From the beginning of her career, fans connected the intense emotions expressed through her lyrics to the little pieces of her life she dared to share—specifically, the pain she experienced in past relationships.

It’s a common source of inspiration for people in Van Etten’s line of work, but she always finds a way to embed her pain not only into her words, but into her note choice and vocal delivery as well. The result has always made fans feel deep, emotional bonds with the singer.

I remember seeing her in concert back in 2014. She started her set without engaging with her audience much; she seemed a little shy and unsure of herself, if I’m being honest. Then, in the middle of the show, she confessed that she was “having a bad day,” to the point, she said, that her bandmates were worried about her. Suddenly, the whole room wanted to give her a big hug and tell her everything was going to be OK.

There were your eyes in the dark of the room the only ones shining the only ones I had met in years it’s not because I always look down it might be I always look out.

You’d hope to God that this impromptu therapy session was authentic. That’s at least how the audience experienced it. But the moment also displayed an element of art that any level of authenticity requires: risk.

I have yet to see a computer program take any kind of intentional risk. In fact, anything it’s managed to do that would be considered risky if done by a human has been labelled a malfunction. But in art, risk is not a malfunction. It’s essential.

What about Dess’ piece?

Let’s pull a few quotes from “Cultural Dopes.”2

“The heroic revolt against industrialism and the romantic belief of art as a sanctuary turned out to be an illusion. Aesthetics alone could not attain the kind of permanence that people sought as solace and refuge from the harsh realities of the world.”

“Post-modernism has failed to offer any values as an alternative to the market place. In fact, post-modern culture is essentially economic. This explains why both social and literary revolt (an unthinkable word these days) have been eviserated since as soon as they make an appearance they are co-opted into movements and fashions and become no more than techniques of oppression in the existing social order.”

“The avant-garde’s role was to usher in the truly groundbreaking work that would overthrow existing conventions and expand one’s consciousness; it was an emancipatory role — one that was cancelled by capital.”

“Today, we are living in hauntological3 times: a stagnant period in which the past is being plundered and it seems impossible that the future will ever arrive.”

“Today, almost every artistic effort inevitably (perhaps unknowingly) re-inscribes the values of the ruling capitalist class.”

First, a rebuttal from Sharon.

I’m not going to include the whole lyric sheet for the song here. Whether you listen or read, know that a rebuttal is in there4.

I’ll make myself a little clearer.

Dess sees capital as a corruptor. He has a point. Artists do “plunder” the past5. Any revolt against societal norms, in art or otherwise, seems to inevitably be “co-opted into [the] movements and fashions” that it initially sought to rise up against.

The cycle of movements in pop music offers a good example of this. Punk rock and grunge developed out of a rejection of the commercialization and self-centredness of their contemporaries (prog rock, disco, radio pop, etc.), only, in time, to be pasterized by the cultural and economic forces that surrounded them. As the major-label products appropriated the costumes of the underground, new artists truly inspired by these movements created the new sounds that amalgamated into the indie/alternative scenes of the late ‘90s and ‘00s, only to restart the cycle all over again.

Dess’ bemoaning about the state of art and culture is a classic example of the Marxist critique of, well, anything. But like most Marxist critiques, it lacks nuance. Dess flies overhead, stubborningly tagging each event and object on a single line.

But culture doesn’t work that way. At the same time that the Simpson sisters were selling out arenas in their fingerless gloves and torn stockings, genuine punk rock was still being written. And I don’t just mean loud, fast rock music6. I mean human beings genuinely expressing themselves through music and lyrics.

There will always be a norm. And a minority will always be there, pushing against that norm. These forces don’t follow each other. They exist simultaneously, often within each of us.

Also: while commerce can threaten artistic integrity, its impact isn’t unavoidably destructive. Commerce is economy, and economy is community.

If it weren’t for capital, I wouldn’t know of Sharon Van Etten or her music, much less be able to use them as examples of authentic art. At this level, Dess is right: to access Sharon’s songs or see her perform, we all need to engage in capitalism.

But how money impacts the integrity of that interaction depends on the artist and the audience, not the exchange of money itself. To say that is to say that money is the only force left in the world, that nothing can rise above or push against it, that capital wins. I don’t believe that. I believe there are forces in our world more powerful than capitalism, and engaging with what Dess calls “pastiche” spurs me on in that belief.

It’s not just music that inspires this faith. On Wednesday7, I watched Women Talking, the film based on Miriam Toews’ novel of the same name that fellow Canadian Sarah Polley just won an Oscar for adapting to the silver screen last week8.

The movie is exactly as advertised, but it succeeds in becoming more than the sum of its parts. In fact, Polley’s decision to focus so intensely on women talking and to leave out elements of the story a lesser filmmaker would seek to exploit for impact is, in large part, the stylistic choice that elevates the film above the norms of its medium.

Watching it, you expect the film to “go there,” and the fact that it doesn’t is what makes it so special. Knowing the power of the story she’s telling, Polley strips out the bells and whistles we expect from a movie, believing that they will soften the story’s blow rather than strengthen it. She takes a risk, and it pays off big-time.

There’s that word again: risk. Women Talking is a perfect example of humans—in art as in life—taking necessary risks. No matter how much power we give over to AI or the “capitalist class,” I don’t think we’ll ever stop taking them. Art will always live in those moments of bravery, and I don’t see any computer program or corporation replicating or diminishing our ability to do that—to be brave.

It's bad, it's bad, it's bad to believe in any song you sing Tell me this even though you can't believe it Tell me I'm wrong

I’m not alone in feeling this way: the legendary Nick Cave responded in a similar, if more impassioned, fashion to ChatGPT’s attempts at songwriting.

Just to be clear, all the emphasis is mine.

Dess says, “The term was first used by Derrida and later developed by Mark Fisher.”

I would recommend you listen.

Though I’d shoot back with a little wisdom from Solomon: “What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the sun.” (Ecclesiastes 1:9)

Although, I also mean loud, fast rock music.

Two days after reading these articles, if you’ve lost track of my timeline here.

Oh, the irony of it.

I might take it a step further and say AI (Midjourney, ChatGPT, all of it) is the logical end to what so many of us have been revolting against for a few years now; namely, generic "content" that's a mile wide, an inch deep, and reads like cardboard. There's no "there" there.

That might be cool for a content mill pumping out amenity descriptions for Best Westerns along the interstate, but for actual writing? No way. ChatGpt's best seen as something of a research intern- and one you still have to keep an eye on.

The only solace I take from the AI apocalypse is that it's almost certainly never going to deliver on its (awful) promise. Though, if it does, I can't see how the future is anything but dystopian.

Beautiful performance by De La and The Roots. I've been rocking De La non-stop for weeks now. What a legacy they leave.